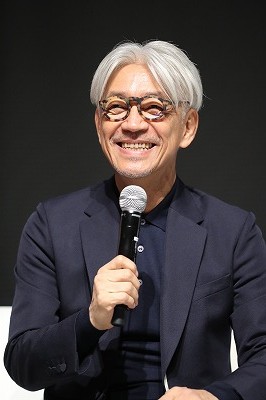

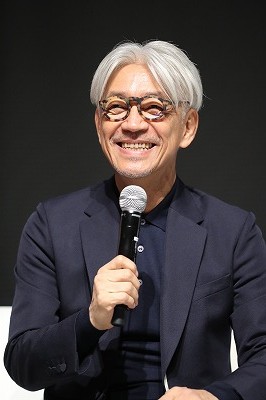

“Am I a samurai?” asked musician-composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, appearing on stage for a talk session on November 1, in honor of his being named the recipient of TIFF’s 4th SAMURAI Award.

©2017 TIFF

His interlocutor, music and literature critic Junichi Konuma, laughed and reassured him that it’s just the name of the award. The two men go way back, with Konuma serving as a guest lecturer on Sakamoto’s NHK Education TV program, “‘Scholar’ Ryuichi Sakamoto’s Music Class.”

Since TIFF is a film, rather than a music, festival, they immediately plunged in, chatting on an extensive range of soundtrack-related topics, from musical grammar and overly demanding directors, to Sakamoto’s evolution as a film composer, and his conviction that music can “save us” in these challenging times.

But the focus of the talk was of course the brilliant Sakamoto himself, and as Konuma prodded him for behind-the-scenes stories about some of his most famous soundtrack projects, the audience was treated to footage — with the musician’s award-winning scores — on a large screen above them.

Sakamoto recalled that his earliest memories of film music were related to Nino Rota’s scores for Federico Fellini’s

La Strada, which he’d heard on the radio and been enticed to see in the theater, and for

Purple Moon. “And also

The Third Man,” he added, humming the familiar lilt.

The two men shared their enduring admiration for Toru Takemitsu, one of the greatest and most innovative Japanese composers, famed for

Kwaidan, The Face of Another and

Fire Festival. “When you’re writing for film,” Sakamoto explained, “You have to make sure the music doesn’t get in the way of the narrative; but you always hope it will be on equal ground and achieve polyphony. With Takemitsu’s soundtracks, the [musical] sound effects are often out of synch, so there’s a relationship between the visuals and the sound that’s unusual and interesting. The frequent elimination of both music and sound is also really interesting.”

After becoming a film composer himself, he admitted that one of the biggest challenges is not being a free agent. “No matter how much we try to sell ourselves and tell directors how much we want to do a job,” he said, “we have to wait for

them to offer the job to

us, just like actors do.”

He described his first such experience, in 1982: “When Nagisa Oshima came to my office with his script for

Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, and asked me to appear in it, I said yes. But I also proposed that I’d like to do the music, too. I don’t know how I had the guts, since it would mean I would be acting for the first time

and composing for film for the first time. But he asked me to write the score, and took a gamble on me.”

Asked how he started creating it, he recalled, “The first thing I did was look at the rough edit on video, and being a total amateur, I listed scenes where I wanted to insert music. Then I compared lists with Mr. Oshima, and there was almost 95% agreement. So he told me to do what I like.”

The film’s theme song — which Sakamoto later recorded with David Sylvian as a pop song, and saw it become a global hit — was a real challenge. “Since it was about Christmas, I thought the theme song should be a Christmas tune,” he explained. “But it took place in the South Pacific, so this Christmas song had to reflect the heat. I thought about it for 2 weeks, and then one afternoon, went to my piano and tried a few things. Then I had a kind of blackout. When I regained consciousness, there was a score! ‘How nice,’ I thought, ‘someone wrote it for me already!’ I still feel like perhaps I didn’t write that myself.”

As for the rest of the film’s music, “I composed using Wagnerian leitmotifs, since there are four main characters, and I thought a lot about the relationships between them. I didn’t want to take a common theme-like approach; I deliberately used repetition. But it was almost like cut-and-paste, since I was such an amateur. There would be all these little pieces of melodies changing throughout a single scene.”

When working on Bernardo Bertolucci’s

The Last Emperor, he remembered, “I took a synthesizer to London to meet with the director, and suggested that it be used for music throughout the film. But he rejected the idea completely. And then David Byrne got to use synthesizers in his compositions [created simultaneously for the film], so I think that was cheating!

“I composed about 45 tunes,” he continued, “and half of them were rejected. Mr. Bertolucci was really strict. I was shocked when I first saw certain scenes [like when the 3-year-old emperor leaves his throne and runs through a billowing yellow curtain, revealing 10,000 men bowing to him in the courtyard], which I wrote really grandiose music for. But Mr. Bertolucci cut it right as the curtain pulls back! I still can’t watch that scene without getting emotional.”

With Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Oscar-winning

The Revenant, which Sakamoto scored in 2015, “The director’s intention was to leave a lot space between the moments of music. I wrote it to be deliberately intermittent, with sounds of nature —glaciers cracking, a distant storm, birds — meant to be inserted in between. This was done so the music wouldn’t become independent, but blend into nature.”

But he admitted there was a lot of conflict with Iñárritu, “arguing back and forth for about 6 months, both of us convinced we couldn’t convince the other. He has a wonderful musical sense, which [is unusual], but we have to follow the director’s wishes, ultimately. It was tough working with him, but Bertolucci was tougher. I once had to rewrite something 5 times for him.”

Sharing the final scene from 1994’s

Little Buddha in which people on three continents scatter the ashes of their friend, a monk, in the air, on land and on the water as an elegiac aria plays, Sakamoto said, “He told me I had to write the world’s saddest song, to make everyone cry their eyes out and make him very rich. The first wasn’t sad enough, the third was too sad, there was no light of hope. I suffered so much and literally, I was rolling on the floor for half a day. Finally, I wrote the fifth one and he liked it.”

But in the end, he admitted, “Anything goes for film music, there are no rules. Some directors are fanatical, but the film industry is full of abnormal people. Maybe that’s why I like it, because I’m perhaps too normal.”

And he recalled his experience at the Venice Film Festival in 2013, when he was a juror and watched over 40 films. “There were three films I especially liked, and I realized that

none of them had music.” He laughed. “I started doubting the significance of my profession for the film industry.”

But the audience knew better. Without the genius of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s compositions for cinema — as well as for the music industry as a whole — film would not speak to us with our hearts, as well as our minds.