Schedule

Tickets

MarketOutline

“I flatter myself that I made a wonderful film!” Japanese anime master Keiichi Hara laughed, talking about his 2013 live-action debut Dawn of a Filmmaker: The Keisuke Kinoshita Story.

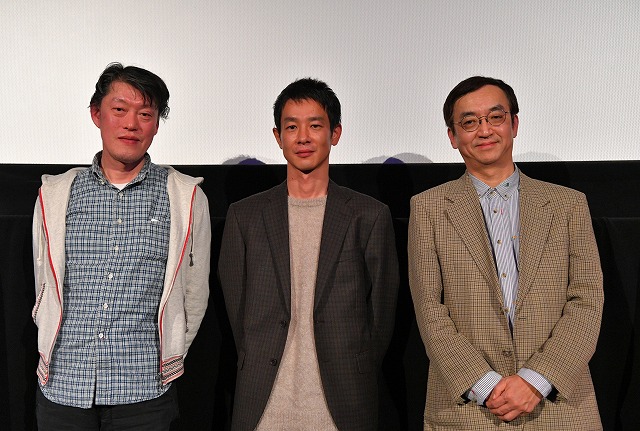

Hara and the film’s star, Ryo Kase, were appearing together at TIFF on November 2, after a screening as part of The World of Keiichi Hara at TIFF, a special section celebrating the creativity of Japan’s singular anime auteur.

Hara noted that it’s a real challenge for an animation filmmaker to direct a live-action film, since the fundamental processes between the two mediums are utterly different. But despite recent examples of crossover failures, such as Andrew Stanton’s John Carter and Sylvain Chomet’s Attila Marcel — Hara fearlessly took on the challenge.

Dawn of a Filmmaker is an unconventional biopic of Keisuke Kinoshita, a renowned filmmaker at Shochiku studios during the golden age of Japanese cinema, whose filmography includes internationally famous work like Twenty-Four Eyes (1954) and The Ballad of Narayama (1958).

“I’m a huge fan of Keisuke Kinoshita,” noted the filmmaker. “To commemorate his centennial anniversary, Shochiku asked me to support some events.” Later, the company decided to revive Kinoshita on screen, and asked Hara to pen a screenplay. According to the director, who was very much satisfied with what he wrote, “I wondered who would direct. It had to be me!!!”

Hara’s script turned out to be no orthodox biopic. Simply constructed and subtly moving, the film depicts Kinoshita’s evacuation to a safer area during the wartime, and his journey across a mountain with a bicycle trailer in which his sick mother is lying. The director’s hardship coincides with his mental struggles with filmmaking, just after Kinoshita’s Army was banned by the authorities due to its wartime sentimentalism.

Hara faced many difficulties making the film. For instance, due to a lack of budget, the producer did not allow him to recreate the air raid at Hamamatsu. “There is not much financial restriction in animation films,” said the director. “I realized the close relationship between screenplay and budget in live-action films.”

Another struggle he faced is that the crew expected the director to decide very quickly whether shots were okay or should be retaken. “Right after I said ‘cut,’ every crew member and actor started looking at me!” laughed Hara, “In animation, there is plenty of time to think.”

That being said, the filmmaker seemed to be extremely satisfied with Kase’s performance and professionalism. According to Hara, “He never compromises. Even after the script was finalized, he came up to me and said, ‘This part should be better in this way.’ And his comments actually made sense.”

The director continued: “Generally, actors want as many lines as possible. In Kase’s case, he often says things like, ‘Maybe this line is not necessary’ or ‘I probably shouldn’t be here [in this scene].’ He always thinks about the entire film.”

Responding to Hara’s ongoing praise, Kase humbly said, “I’m just not a flexible actor. I need to know where my character is heading.” Still, Hara, jokingly disagreed, saying “He is such a wonderful actor that even Abbas Kiarostami, Takeshi Kitano and Clint Eastwood wanted to work with him.” “Please stop,” Kase bashfully responded.

Yuko Tanaka, playing the mother of Kinoshita, also astonished the director on set. During shooting of a close-up in which Tanaka’s character is looking up at the night sky, she asked the boom operator to move the microphone away from her. Hara recalls this moment: “She said, ‘I want to look at the moon.’ I was so touched.”

Sharing one anecdote after another, Hara, who seemed even more extra-cheerful than he usually is, had more stories to tell but only a 20-minute post-screening session. Reluctantly concluding the talk, he told the audience, “I respect Kinoshita most, more than any other filmmaker. Please be sure you watch his classics. […] No one at Shochiku forced me to say this.”