Schedule

Tickets

MarketOutline

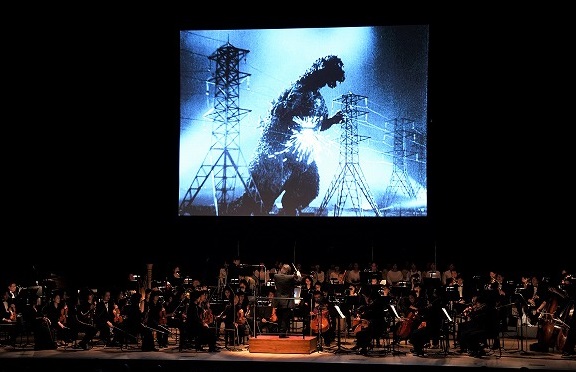

Live movie concerts are all the rage in the West, and with TIFF’s Godzilla Cinema Concerts on October 31, they’re sure to begin catching on in a big way in Japan, too.

Marking TIFF’s 30th anniversary this year, as well as the upcoming Japanese release of Toho’s 30th film in the Godzilla franchise on November 17, the festival celebrated with two screenings of the digitally restored, English-subtitled original Godzilla (1954), accompanied by the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra performing the iconic soundtrack written by pre-eminent composer Akira Ifukube. Conductor Kaoru Wada, a pupil of Ifukube’s, directed the musicians, practically creating sparks onstage with what is considered one of the finest film scores ever written.

The day’s embarrassment of classic riches began with a short talk event that brought together for the first time three generations of Godzilla series creators: Heisei series producer Shogo Tomiyama, Shin Godzilla director Shinji Higuchi, and music producer Masao Iwase.

Tomiyama, who is now the Secretary-General of the Japan Academy Film Prize Association, took the reins of the Godzilla series following original producer Tomoyuki Tanaka’s death, and presided over 12 films between 1989 and 2000 before taking a break, then returning in 2004 to write and produce the biggest title to that date: Godzilla: Final Wars (2004). Last year, as the world knows, visual effects wizard Higuchi (Attack on Titan) stepped in to codirect the latest iteration, Shin Godzilla, with Hideaki Anno, and made tokusatsu history (No. 2 at the 2016 box office, with over $75 million). From 1983-2010, music producer Iwase produced 45 scores for Toho films, including Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989), Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991) and Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992).

Iwase, who also produced TIFF’s live cinema concerts, noted that, unfortunately, “only Godzilla and Castle of Sand can be performed in this way in Japan. Because US films are recorded on separate channels and Japanese films are not, it’s not possible to remove the film’s music and enable a live orchestra to be heard along with the original voice track.” He described the process of recording: “I wasn’t there 63 years ago, but in those days, you would get together about 50 members of orchestra and record while they’re watching the film unfold on a screen, and it was a one-time recording.”

Tomiyama concurred, recalling that, “When I worked on Godzilla vs. Biollante [9 years after the last Godzilla film had been made], we decided not to use Mr. Ifukube’s music. My boss, Mr. [Tomoyuki] Tanaka, felt that since it was a new start, we should do it in a new way. But when we heard the new music in the theater, we realized that Mr. Ifukube’s score was an absolutely perfect match.

“So we went to him and asked if we could once again use his score for the new series. Mr. Ifukube said the conditions had to be the same: that it would be a one-time recording of the score. It cost an awful lot to bring in all the musicians and the equipment, but that’s what he wanted, so that’s how it was recorded.”

Iwai explained that certain adjustments had to be made for the day’s special live performances. “Yesterday I watched the film again and found that there were scenes with the music turned off,” he said, “such as the scene where Godzilla walks into the electrical wires and the lever is pulled to jolt him. Actually, Mr. Ifukube wrote music for the entire scene but it was cut out by the sound editor. We decided that we should respect him and leave his music in when we play it today.”

Higuchi told the audience that he didn’t even have to think about whether or not to use Ifukube’s music for Shin Godzilla, since “[Hideaki] Anno already included the music cues in the script.” He continued, “I saw Godzilla in many theaters, on VHS and on other formats over the years. My favorite musical moment is at the end when Dr. Serizawa sacrifices himself to protect his secret weapon [the Oxygen Destroyer], and dies in Tokyo Bay. The music is so vivid, and that really revealed for me the power of music. It made me cry. It’s truly amazing.”

And with that, the three generations of Godzilla intimates left the stage and the film began with… several silent moments of anticipation as the credits rolled… before the incredibly thrilling, driving beat of the Godzilla theme began. Right up there with the Jaws theme, Ifukube’s creation came to full-blooded life. It is far more spare than remembered, as well as elegant and at certain moments, heart-pounding. Heavy on horns and thrumming strings, its repetition in the film ratchets up the excitement, but seems at times to speak for the monster itself.

With the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Lucky Dragon 5 incident (in which a fishing boat was irradiated during Bikini Atoll H-bomb testing) not yet distant memories, Godzilla was conceived by Toho producer Tomoyuki Tanaka, director Ishiro Honda and SFX director Eiji Tsuburaya as a metaphor for nuclear weapons. Gojira, the Japanese name for the beast and the series, is a portmanteau of the words gorira (gorilla) and kujira (whale), since he is immense and lives at the bottom of the sea. The creature is also often called King of the Monsters, a description first used in Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956), a heavily re-edited “Americanized” version of the original version, which erased all connections to the monster’s nuclear origins and featured narration and additional footage starring Raymond Burr.

Godzilla almost instantly became a pop culture icon, and it has now starred in 29 films produced by Toho in Japan, as well as three films in Hollywood. On November 17, Toho’s 30th title in the franchise will be released in Japan, the animated feature Godzilla: Monster Planet.

Watching it today, just 6 years after the triple disaster in Fukushima in 2011, its anti-nuclear themes resonate: the government wants to keep Godzilla a secret, while the press argues that it must be made public; and scientists want to research the creature, to learn from it, rather than killing it. Japan’s wish for “peace and light” comes through loud and clear, especially when the Chor June choir group begins performing the elegiac hymn “Pray for Peace” as Godzilla renders Tokyo a sea of flames on the screen above them.

The Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra performed a rousing encore, a very special arrangement of Ifukube’s monster film music “Monster Fantasy,” before the lights came up and the magic had to end.

Godzilla may not have been the first Jurassic creature to grace cinema screens, but 63 years later, it remains the most indelible — and most enduring.