Schedule

Tickets

MarketOutline

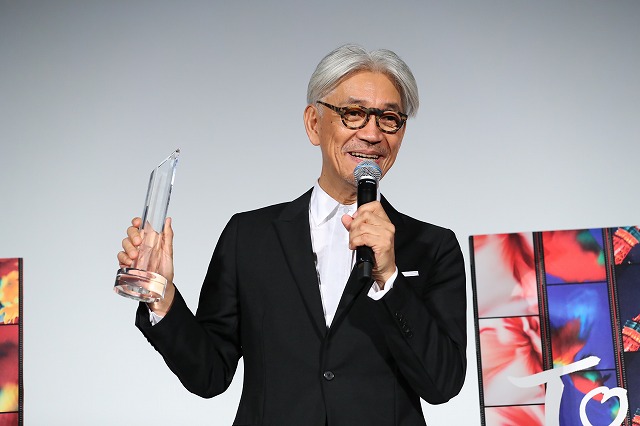

Acclaimed musician-composer Ryuichi Sakamoto received TIFF’s 4th SAMURAI Award on November 1 in an enormous theater at Roppongihills packed with an SRO crowd, becoming the first honoree who has never directed a film — as well as the first to bring a measure of levity to the proceedings.

Although it was clear that he took the award seriously, upon receiving his crystal trophy from Festival Director Takeo Hisamatsu, he found it impossible to resist goofing around with it. “There’s a katana sword engraved on this trophy,” he told the audience with a big smile, pretending to be stabbed, striking a heraldic pose, waving it above his head, testing the sharpness of its tip. “It reminds me of the sword I used in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. I had to spend eight days in a dojo learning how to use it. Of course, the swords we used in the film weren’t real, but when you get a sword, you always want to play around with it. We chopped down so many trees on the Pacific island where we were shooting. Since that was 35 years ago, I wasn’t as environmentally conscious as I am now. These days, I’m working to preserve trees and plant more of them.”

The SAMURAI Award commends achievements by veteran filmmakers and other creators who continue to contribute groundbreaking work that carves pathways to a new era in cinema. Sakamoto joins a stellar group of previous award winners — Takeshi Kitano and Tim Burton in 2014, Yoji Yamada and John Woo (2015), Martin Scorsese and Kiyoshi Kurosawa (2016) — selected by TIFF for the recognition. The groundbreaking composer (Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, The Last Emperor, The Sheltering Sky, Revenant) has received BAFTA, Oscar, Grammy and Golden Globe awards for his film music, along with a slew of other prizes and honors.

“Tonight you’ll be seeing my documentary, and I want to thank you all for being here,” he said, and then corrected himself. “Well, it’s not my film, I’m the main character, I didn’t make it.”

He was then joined on stage by New York-based Stephen Nomura Schible, director of Ryuichi Sakamoto: CODA. Speaking in fluent Japanese, Schible recalled, “We started shooting in the summer of 2012, and it’s nice to see many people affiliated with the film in the audience. Mr. Sakamoto always says that the film belongs to the director, but I wouldn’t have been able to make it without everyone’s help.”

Sakamoto admitted, “I don’t particularly like revealing my true self to people, so you might wonder why I allowed this film to be made. As you see, Mr. Schible is very humble, very polite, very Japanese, and I was attracted to his personality. As time went by, a lot of things happened, and then I got sick. I’ll bet he was thinking, ‘This will make it so dramatic!’ The film and the budget kept growing and before we realized it, 5 years had passed.”

Schible reassured him, “I was also a producer on the film, and the budget didn’t get that big.” He continued, “In the beginning, we were groping around to see what was best, but as Mr. Sakamoto said, before we realized it, all those years passed and it had taken essentially the shape we have today.”

Before director and star left the stage, Sakamoto couldn’t help marveling at the size of Toho’s extra-large screen. “I saw Godzilla on this screen last year. I hate to think of my face being projected that huge,” he laughed, half-bowing in apology to viewers.

Schible’s CODA is his second feature music documentary, following Eric Clapton: Sessions for Robert J (2004). Although the film covers 5 years (30, if brief archival scenes count), at its heart is the year in which Sakamoto is on a forced hiatus from work and performing, having been diagnosed in 2014 with oropharyngeal cancer and begun treatment. Reflecting this monumental turning point in his life, the film presents an exceptionally subdued, contemplative Sakamoto, a man worrying about his mortality, but still eager to do meaningful work. “I want to write music I won’t be ashamed to leave behind,” he says, “but I’m constantly bumping up against my own limitations.”

Yet his playful side does emerge in several scenes. In one, he is recording sounds around the house during a rainstorm, and dissatisfied, finally sticks a bucket over his head and steps outside into the downpour. In another, he has journeyed to the Arctic Circle to see the effects of global warming, as well as to record sounds (a ceaseless habit) amidst the “pre-industrial era ice” of the glaciers, and begins “fishing sound,” dipping a rod with a microphone attached into the frigid Arctic waters.

We see the musician pottering around the house, playing the piano, mixing sounds and music on his Pro Tools system (creating what he calls “auditory texture,” in pursuit of “sonic blending, both chaotic and unified”), and finally, cautiously beginning to work again. In 2015, Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu approaches Sakamoto to ask whether he would like to write the score for The Revenant. “I’m still supposed to be on hiatus,” he admits, “but I couldn’t say no, because I admire him too much.”

Sakamoto is also shown visiting Japan, where in 2012, he is in Fukushima to perform for the 3/11 evacuees and other victims. He seems especially taken with a “tsunami piano,” which has survived the disaster in Futaba, floating up above the water. “It felt like I was playing the corpse of a piano that drowned,” he describes it; “it was strangely bright but also melancholic.”

Soon after, he is in Tokyo organizing a No Nukes concert, and takes part in one of the frequent anti-nuclear demonstrations. “We must brave ourselves for a long battle,” he tells a huge crowd of protestors gathered around the National Diet Building. “I’m here because it would have been stressful not to speak my mind. I can no longer look the other way.”

The 3/11 experience in Japan reminds him of his 9/11 experience in New York. He was home in the West Village when the World Trade Center toppled, and as he recalls, “The music vanished from Manhattan for a week.” When he hears a guitar a week later, he is stunned to realize, “Even I, surrounded as I am by it, hadn’t noticed that music was gone.”

Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda opens in Japan on November 4.